My dad used to tell a story about my mom’s early days in the U.S. Popcorn was new to and she loved it. One evening, when he was out with friends, she decided to make some for herself—but she forgot to put the top on the pan and when the popcorn started popping it went everywhere. We thought this was hilarious, a little like something that might have happened on “I Love Lucy.”

It occurred to me after rereading Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn then reading its sequel, Long Island, that my mom never told this story, only my dad.

She was embarrassed by it. She was also embarrassed by her English accent, which people found charming. “I love how you say ‘banana’,” they’d say. And by mistakes she made because some words were used or pronounced differently in England than in the U.S.

“She’s so homely,” she said of a woman she met—meaning nice, easy to be with. Mortified to learn it meant “ugly” here.

When she said she wanted to buy an aluminum saucepan in a department store, the salesclerk said they didn’t have any—when there was a display of them nearby. She left, feeling that the clerk just didn’t want to serve her. When she told my dad—pronouncing it as she had at the store: “al oom IN yum”, he explained the clerk’s confusion. Another funny story.

Eilis Lacy, the young Irish woman in Toibin’s novels, immigrated to the U.S. under completely different circumstances. Jobs are scarce in post-war Ireland. With the help of Father Flood, an Irish priest who lived in Brooklyn, her widowed mother and older sister make arrangements for Eilis to move there because more opportunities will be available to her. She’ll be safe; Father Flood will watch over her. And he does. (It’s not that kind of story.)

Eilis doesn’t want to go but feels she has no choice.

Father Flood finds her a room in a reputable boarding house for women and finds her a job as a salesclerk in a department store. In time, he enrolls her in night school to study bookkeeping. Still, she’s dreadfully homesick. She doesn’t particularly enjoy outings but when Father Flood organizes a series of Friday night dances in the parish, she feels obligated to attend. One night she meets Tony Fiorella, who falls madly in love with her. She thinks she loves him, too. But even though she’s not sure, when something happens that calls her back to Ireland for a month, she tells him she does and makes a promise to him.

I’ll stop here other than to say that her time in Ireland makes her question that promise.

We see Eilis again at forty, in Long Island. She’s married to Tony, with two teenage children; he has a successful plumbing business. They live among Tony’s huge, extended family in neighboring houses on a cul-de-sac on Long Island. She hasn’t returned to Ireland for decades.

The book begins:

“That Irishman has been here again,” Francesca said, sitting down at the kitchen table. “He has come to every house, but it’s you he’s looking for. I told him you would be home soon.”

“What does he want” Eilis asked.

“I did everything to make him tell me, but he wouldn’t. He asked for you by name.”

What he wants to tell her is:

“He fixed everything in our house…He even did a bit more than was in the estimate. Indeed, he came back regularly when he knew the woman of the house would be there and I would not. And his plumbing is so good that she is to have a baby in August.”

Yikes! There’s a beginning that works on every possible level!

He’s not about to raise the baby himself, he tells Eilis.

“As soon as this little bastard is born, I am transporting it here. And if you are not at home, then I will hand it to that other woman. And if there’s no one at all in any of the houses you people own, I’ll leave it right here on your doorstep.”

Eilis is shocked and furious. The one thing she thought she knew for sure was that Tony loved her; she’d sacrificed so much not to break his heart.

She’s not about to raise this baby either.

Again, I’ll stop—other than to say that, needing to get away, she decides to visit her mother in Ireland, where, what caused her to question her love for Tony comes back to roost.

I love these two novels. They’re gorgeously written, bringing life in all three settings vividly to the page. The characters, as complicated as real people.

Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about what it must have been like for my mom to immigrate to America after the war, but Toibin’s novels made think about her experience a bit differently—or, maybe, to feel it in a way I hadn’t felt it before.

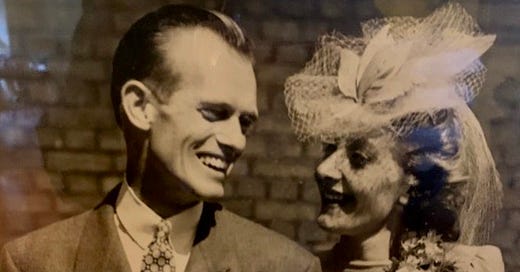

Her experience was nothing like Eilis’s. She was a war bride; the decision to come here was hers alone.

Though, I wish I had asked her what she thought it was going to be like.

What I know now is that every family but your own is like a foreign country, with its own rules, traditions, and hierarchies, as well as a backstory you can never fully understand—even if you lived next door to them all your life. My mom had to find her place in a new, complicated family at the same time she was trying to find her place in a new world—and, sadly, never quite found her place in either.

She never became an American citizen. Maybe because she was intimidated by taking the test, maybe (I hope this was the reason) because she never stopped thinking of herself as British.

She returned to London only twice during the time I lived at home, once with me, when I was two; once to attend her mother’s funeral, when I was sixteen.

I wonder now who she might have encountered from her girlhood there, what it might have meant to her. I wonder what losses she might have suffered during the war that put her in my father’s path.

She was a ballroom dancer before the war and had a partner with whom she entered (and won) competitions. Who was he?

I’ll never know.

But I’m glad to have read these two novels that, for a moment, made me feel what she might have felt so far away from home.

Thanks.

I'm pretty sure you'll love it!