A while back, invited to give a talk on a short story from a writer’s point of view, I chose my all-time favorite story, Edith Wharton’s “Roman Fever.” But I put off and put off preparing the talk until the date to give it was just a month off—three weeks of which I would be traveling in France. All I could do was put the story in my suitcase and pray to be struck by inspiration while I was away.

On that trip I read “Roman Fever” in countless cafes over coffee and croissants, on the Metro, on trains traveling to Chartre, Giverny and Rouen. I read it on a bench in the Luxembourg Gardens and stretched out on the grass in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. I read it in bed each night, drifting into sleep.

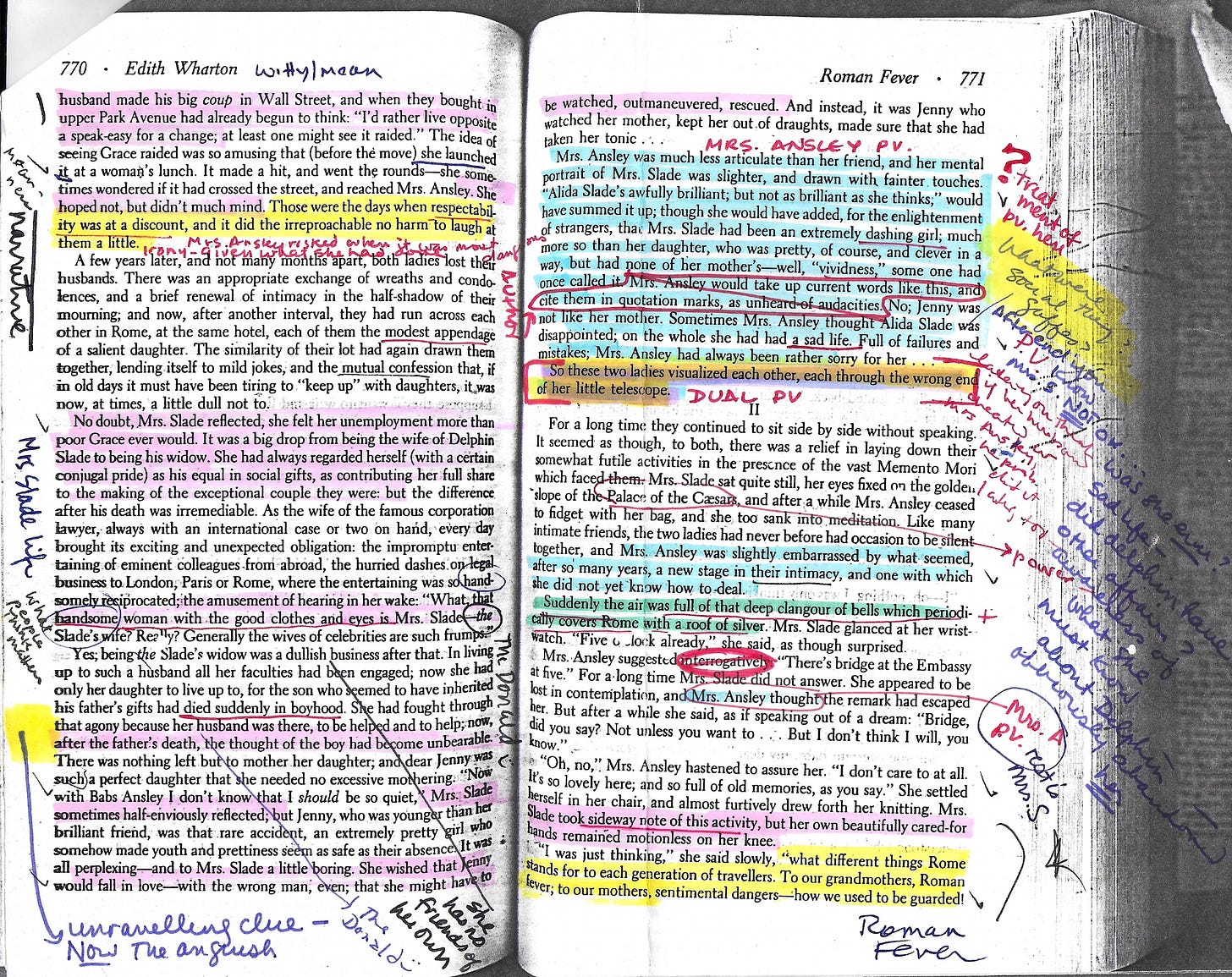

Every time I read it, I saw something new. The margins of the story were crowded with my notes, the body marked with underlining, circled phrases, exclamation points and stars.

What do I know, I asked myself. Where, on the page, is that revealed?

How do I feel? What are the words doing on the page to make me feel that way?

In time, after who-knows-how-many readings, the skeleton of the story revealed itself. I began to understand how “Roman Fever” worked, how it moved. Thus, the substance of my library talk revealed itself to me: while the literary analysis of a story is useful to an academic, a writer benefits more from looking closely, observing how the words on the page work to create its world.

When I got home, I got out my highlighters and tracked various elements of the story—characterization, dialogue, setting, transitions, tension cranks and flashbacks. I highlighted point-of-view shifts, places where crucial information was conveyed, where the story was told through narrative, where through scene. When I’d looked at every single thing, I laid the pages of the story out like a long rug and understood, suddenly, viscerally, that in good writing the elements of fiction are simultaneously in play.

My marked-up story was like rich, textured piece of weaving in its overall effect. There were occasional small chunks of description or narrative, identified by their highlighted colors, but most paragraphs (and even single sentences) showed a blend of the colors I’d chosen to identify the aspects of the story I was looking at. I could see how Wharton had created Rome in six bits of description, each no more than a paragraph, sprinkled throughout the story. How, starting on the first page, she planted “clues” that cranked tension and crab-walked the women toward the shocking revelation of the last line.

I was reminded of “Roman Fever” when I finished reading Michelle Hunevin’s Bug Hollow.

The stories couldn’t be more different. “Roman Fever” brings the secrets and lies between two “women of a certain age” that have been festering for years to a head. It crab-walks to its explosive end, making us privy to each woman’s point of view in bits and pieces along the way—a comment here, a memory there, a little disagreement about what happened when.

Bug Hollow tells the story of what happens to a family in the aftermath of a tragic loss, moving from one point of view to another down through time in whole chapters—each arc its own story as well as part of the larger story about family itself.

What they have in common for me is this: I was fascinated by their effect on me. I wanted to know how they were made.

Bug Hollow begins with eight-year-old Sally, the youngest child in the Samuelson family, on the day her brother, Ellis, newly graduated from high school, takes off on a road trip along the California coast with some friends. He doesn’t come back when they do. He’s fallen in love with a girl, Julia, at a commune called Bug Hollow and has decided to stay for the rest of the summer. When he refuses to return, the family goes to get him. But he’s different. Sullen, in the few weeks before he leaves for college. Then, days after he gets there, he dies in a freak accident.

The rest of the book, subtly and not so subtly, charts the effect of his death on those who loved him and some who didn’t even know him but whose lives were shaped in large and small ways by his death. Among them—

Julia, Ellis’s girlfriend, pregnant with his child. Sybil, his mother, who pours her energy into trying to save the troubled children in her classroom while becoming more and more distant from her own. Katie, the middle daughter, a resentful high-achiever. And artistic Sally, emotionally responsible for…everyone.

I had a little trouble adjusting to the huge leaps in time in Bug Hollow. I’d come to the end of a section and think, I want more. A couple of times a new character popped into the story, which I found jarring. In fact, I wasn’t sure how I felt about the book when it was over.

But I kept thinking about it, I kept feeling it—the grief, the walls that go up because of it, the mistakes and misunderstandings, The way joy can be born from the worst, most devastating occurrence.

The thing is, in the end, I knew everything I needed to know about each character.

Somehow, I knew what I needed to know about what happened in between those gaps of time.

(An example of Hemingway’s idea that a story itself is just the tip of the iceberg of what lies below the story, what the writer knows—and it’s that stuff below that gives the story it’s depth and power?)

If I had a lot of time, I’d read and reread Bug Hollow and try to figure out how it works. There’s a lesson there for anyone who wants to write a novel, for sure.

This book stayed in my mind, which is what all novelists I know want their novels to do.

The book sounds interesting. I also appreciate the way you describe your own process for understanding (from a writer's perspectvie) what makes someone else's story tick. I have a small cupboard of old yellow-paged books that I don't want to toss yet. The books are filled with my notes from year after year of re-reading and then teaching these books in my classroom. They look a lot like your picture. As always, I appreciate your offering here.

I love seeing a picture of your marked up copy! That is beautiful!