My friend Daly Walker, a writer and retired surgeon, recently gave a talk about narrative medicine, which draws on storytelling to enhance medical students’ listening and observing skills, teach empathy, and encourage them to consider more more than just the medical histories of their patients. It’s a relatively new field, though good physicians have been practicing it forever. Dr. Robert Coles shows it at work in his wonderful book, The Call of Stories: Teaching and the Moral Imagination (1990), relating personal stories about how listening to patients’ stories contributed crucial information for diagnosis and care. He believed in the power of fiction, too, and regularly taught literature classes to medical students to prepare them for the complicated, gut-wrenching decisions they’d have to make one day.

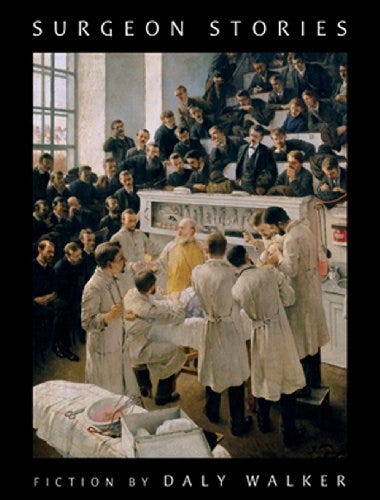

Daly Walker writes this kind of story. The physicians in his two short story collections, Surgeon Stories and The Doctor’s Dilemma, find themselves in a variety of predicaments—dealing with a mother, a Jehovah’s Witness, who refuses the blood transfusion her son needs to survive, the implications of treating a murderer on death row, the temptation not to take every measure possible when a daughter’s abusive boyfriend is brought to the emergency room in critical condition after a motorcycle accident. Walker’s stories about doctors are so deep and finely tuned you feel you’re right there with them, bearing the terrible weight of all those lives depending on your expertise and compassion.

My favorite of Daly Walker’s stories is “I Am the Grass,” in which a Vietnam vet, now a successful cosmetic surgeon, returns to Vietnam to repair the cleft palates of children twenty years after serving there. It begins,

“Because I love my wife and daughter, and because I want them to believe I am a good man, I have never talked to them about my year as a grunt with the 25th Infantry in Vietnam. I cannot tell my thirteen-year-old that once, drunk on Ba Muoi Ba beer, I took a girl her age into a thatched-roof hooch in Tay Ninh City and did her on a bamboo mat. I cannot tell my wife, who paints watercolors of songbirds, that on a search-and-destroy mission I emptied my M-60 machine gun into two beautiful white egrets that were wading in the muddy water of a paddy. I cannot tell them how I sang "Happy Trails" as I shoved two wounded Viet Cong out the door of a medevac chopper hovering twenty feet above the tarmac of a battalion aid station. I cannot tell them how I lay in a ditch and used my M-60 to gun down a skinny, black-haired farmer I thought was a VC, nearly blowing his head off. I cannot tell them how I completed the decapitation with a machete, and then stuck his head on a pole on top of a mountain called Nui Ba Den. All these things fester in me like the tiny fragment of shrapnel embedded in my skull, haunt me like the corpse of the slim dark man I killed. I cannot talk about these things that I wish I could forget but know that I never will.”

Whoa, right?

Not long after the doctor, never named, arrives at the hospital, he’s summoned by the hospital director, formerly a surgeon in the North Vietnamese army, who lost both thumbs to torture by South Vietnamese soldiers. He wants the doctor to perform a delicate, risky, virtually impossible surgery, transplanting a toe to reconstruct one of them.

The story goes back and forth in time, from the doctor’s stint in Vietnam, to his homecoming, to his life as a medical student, a physician, and a husband and father, to the operation and its outcome. It is harrowing to read. You feel the desperate hope of this troubled man for some kind of atonement as the story moves inch by inch through the landscape of his past.

It’s one of the best stories about the Vietnam war I’ve ever read. I’ve taught it dozens of times and it gets me every single time.

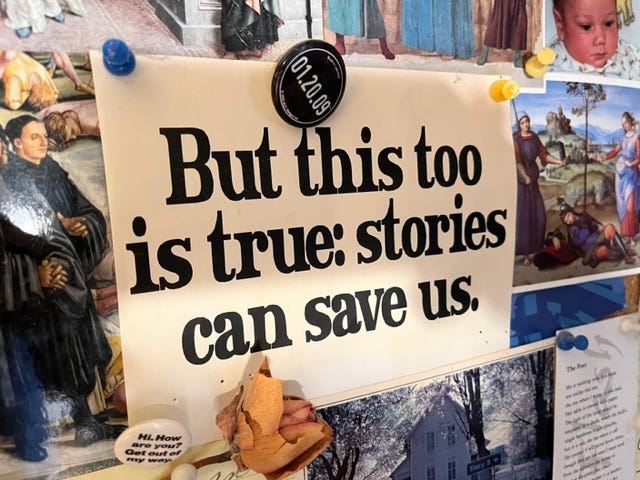

Tim O’Brien also writes gorgeously harrowing stories about Vietnam. The first line of my favorite, Lives of the Dead, is pinned to my bulletin board, where I see it every day.

Thanks for the tip. I'll put it on my to-read list.

This is a wonderfully written piece about a terribly difficult subject to tackle. It feels timely to me, as well, since my family has had some bad experiences with our nation's, and our state's, utterly broken health care system. The very idea of narrative medicine--that bridging of the gap between the sciences and humanities--has probably had a tough time establishing itself in such a transactional system. It's good to hear that physicians with the skills to write and to otherwise employ story to improve their practice and help their patients exist. I'll certainly put Daly's work on my list to read.