I have a regrettable moral streak about certain, mostly ridiculous things, and for the longest time I refused to listen to audio books. You had to hold a book in your hands, read—actually read—the words on the page for it to count. Then one day, dreading a long, solitary car trip, I picked up the audio version of Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women at the library. I loved that novel; I’d read it several times. I told myself it wouldn’t be cheating to listen to it, just to see what listening to a book felt like.

Soon, there I was, zooming along the interstate, laughing my head off at the misadventures of Pym’s spinster ladies, which were all the more hilarious for the crisp English accent narrating them. The miles sped by; I was a little sorry to arrive at my destination before the book was over.

I can’t remember when that was, but I know I was listening to cassette tapes. Then, later, CDs. Now, miraculously, I can download books on my iPhone, instantly available when I have a moment to listen.

I’ve become bit of a zealot for audio books over the years, haranguing my fellow readers who are still reluctant to give them a try. You feel lost in inside the book, just as you do when you’re when you’re reading, I say—and a really good narrator adds a whole new dimension to the story.

Not to mention, you can pretty much read 24/7, if you’re so inclined—and I am.

I listen to audio books in the car, walking the dog, cleaning the house, working in the yard. It makes all those tiresome necessities easier somehow.

Not that I’ve given up the sublime pleasure of curling up with an actual book. Never! That will forever be my preferred encounter with a novel. In fact, sometimes I love an audio book so much I curl up and read the actual book, too, so I can linger over the words on the page.

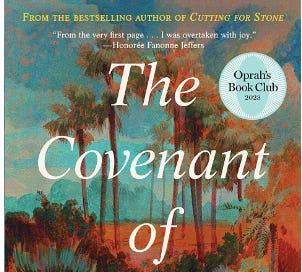

I might just do that with Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water, a gorgeous novel set in southern India. It begins in 1900 with twelve-year-old Miriamma and her mother sorrowfully anticipating the morning, when Miriamma will be sent by boat to marry a forty-year-old widower whom she has never met. Grieving the recent death of her father and the separation from her mother, Miriamma arrives at his estate in the town of Parambil, fearful and lonely.

I was fearful, too, knowing what all too often happened to young women in similar situations. But a gentle elephant, Damo, pokes his trunk into her quarters to welcome her. She falls in love with her toddler stepson JoJo. She feels safe in the presence of Dolly Kochama, who comes to teach her the ways of her new world. And her husband quietly keeps his distance. Soon she feels a part of the small community of Parambil, which includes a colorful cast of characters, like Decency Kochama, Lenin Evermore, Baby Mol and the spirit of JoJo’s mother, who becomes Mariamma’s protector.

I’d have been happy to stay in magical Perambil, with all its joys and sorrows, living with Mariamma as she matured, fell in love with her husband, had children of her own and, in time, became Big Ammichi (mother)—the matriarch and manager of the family estate.

But the book ranges far beyond Perambil, circling back again and again, as it follows three generations of Mariamma’s family and the curse of water that has caused death by drowning for as long as anyone can remember. It feels mystical; curses always do. Yet slowly, over the passage of more than seventy years, Verghese, a doctor himself, brings the reader to a medical understanding of this strange affliction by way of a network of characters, whose lives we also inhabit. There’s Digby Kilgour, a Scottish surgeon who emigrates to work in the British Indian Medical Service after a scandal; Rune Orqvist, an elderly Swedish doctor who decides to live out his days in service to a leper colony, and Big Ammichi’s namesake, Miriamma, who becomes a doctor in hopes of discovering the source of the curse that has caused such sorrow in her family.

I cannot possibly do this novel justice. It’s too big, too rich with history, culture, curiosities, and marvelous segues that seem random until they connect and branch out, ultimately coming together in an ending that is at the same time shocking and inevitable.

But I’ll say this. I avoid super-long novels; years of reading have taught me that they are almost always full self-indulgent segues and trips down rabbit holes of research the reader must wade through to get to the point of the story.

The Covenant of Water was 700+ pages (30+ hours of listening!) and I was never once bored. Every change of point of view, every new location, every new character with a long story about how they got to the moment in the book where they appear drew me in deeper and deeper. The narration—by the author, in his lovely, musical Indian accent—was superb.

While I was listening to The Covenant of Water, I caught up on errands I’d been putting off, always driving the long way. I did considerably more yard work than usual; my dog Lewis was delighted by the number of walks we took.

When it was over, I felt as I do when I come home from a long, wonderful trip. For a few days, part of me is still there, the other part is here, wishing I could go back.

As Big Ammachi’s son Phillipose, an avid reader, said, "Ammachi, when I come to the end of a book, and I look up, just four days have passed. But in that time, I've lived through three generations and learned more about the world and about myself than I do during a year in school. Ahab, Quee Queequeg, Ophelia, and other characters die on the page so that we might live better lives."

Thanks! I've thought about going back and forth like that. Maybe I'll try it.

I'm pretty sure you'd love it!