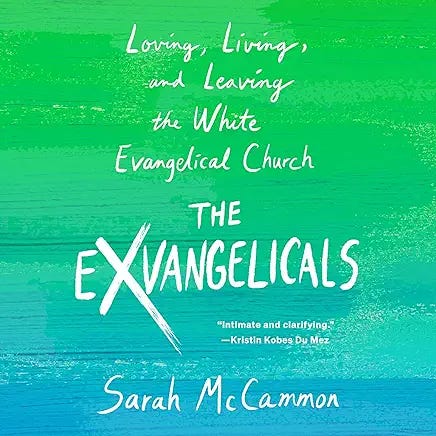

Sarah McCamman’s The EXvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church tells the story of the author’s experience growing up in a strict Evangelical family. It also tells the stories of others who left the church and forged new lives, sometimes remaining connected to their families, sometimes not.

Listening to it made me think of the role of religion in my own life and of the many people I’ve known over the years whose lives have been damaged by religious upbringings in the Christian church.

Nobody in my extended family was ultra-religious, though my aunts and uncles attended a Presbyterian church. We went on Easter Sunday: there are photos of us, and I remember pitching a fit one Easter because I didn’t have a new dress to wear.

Sometimes my dad dropped me off there for Sunday School. I probably enjoyed it when I was little—I loved school—but remember being a bit intimidated as I got older by not knowing the Biblical stories that other kids knew.

And I had questions! Like, Were Adam and Eve cave people? If your husband died and you married someone else, who would you be with in heaven?

We didn’t say prayers before bedtime (or any time) in our family, but I remember being frightened by the childhood prayer that ended, “If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take.”

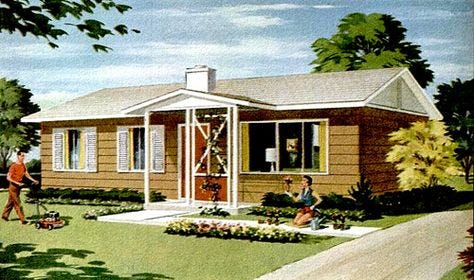

When I was nine, we moved to one of those post WW2 subdivisions that sprang up all over America—block after block of little square houses. There were more than sixty kids on our block alone—the majority of them Catholic. Presbyterian Sunday School had been vague about guilt. I’m not even sure if guilt was mentioned. The message was: Be Good. Maybe they figured you’d just naturally feel guilty if you were bad—and left it at that.

Catholicism, interpreted by the neighbor kids, was my introduction to “official” guilt—guilt for sin as opposed to guilt for just behaving badly. Not to mention the reality of hell! But it seemed unfair that they could go to confession and start all over while I just kept piling up guilt and feeling worse and worse.

Still, I loved those scapulars they wore and the little cards with pictures of the saints.

And nuns fascinated me. Walking to school, I walked past Our Lady of Perpetual Help and I’d see them sometimes hurrying from the convent to the church in their habits. (Possibly the seed for my love of voluminous black dresses) I’ve been fascinated—well, maybe a bit obsessed—by nuns ever since and love observing them every summer in Assisi.

When a Pentecostal church was built not too far from our neighborhood, my dad forbade us to go anywhere near it. But sometimes on a summer evening my friend and I would ride our bikes and sit outside and listen to the singing. “Holy Rollers” we called them. Rumor was there were snakes involved in their worship and sometimes they just started speaking in weird languages. It was thrilling to be there as the sun started to go down.

By the time I got to high school, religion wasn’t in the picture at all. I sort of believed in God, but wavered when I started thinking about…logistics.

Did God really care whether that Catholic kid who crossed himself before attempting a free throw succeeded?

Then, in college, I fell in love with a very lapsed Missouri Synod Lutheran—and that was the end of Christianity for me.

Not a happy, character-building history. But not damaging, either.

I’ve thought about faith a lot over the years, though—faith versus religion, which seem to me two different things. Teaching high school, I observed many of my students—some very much involved in church and church activities, others rebelling against religion, struggling with what to believe.

One very bright students wrote in her journal that she was troubled because, freewriting, questions about her faith bubbled up.

I wrote in the margin, “God gave you a questioning mind. I believe he expects you to use it.”

The summer after her freshman year in college, she asked me to critique an essay she’d written. It began, “I asked God to give me a break” and proceeded to tell the story of rethinking religion to better fit her widening world.

It made me really happy.

I wish the struggling kids would have had The EXvangelicals to help them understand how they were shaped but this paradoxical culture of purity and hate. To know they’re not alone in their struggle and that there are many out there who’ve left and survived. Even found the path to a loving God.

I have great respect (and a measure of envy) for people of true faith. By which I mean those who live Christ’s teaching. And I have great compassion by those damaged by being brought up in a religion focused on fear and hatred and made their lives so rigid and small that, escaping it was like finding themselves on a whole new planet.

A few years back, a friend asked me to contribute to a literary magazine he’d cofounded that explored writers’ relationships with faith and religion. It seemed to me that I didn’t have much of a relationship. But he said, “Do it anyway.” So I did, surprising myself, as I often do when asked to write something I’d never have thought of writing on my own.

Dear God,

Okay, first, full disclosure: I don’t believe You are a You.

Of course, if I’m wrong and You are a You, You already know this—and everything else, for that matter. And if You really are the all powerful You so many people imagine, the one with long white hair sitting on a throne in heaven (wherever that is), maybe You’ve got Your finger raised right now, trying to decide whether to unleash that lightning bolt to smite me for being insubordinate.

Or.

Maybe You’re thinking, Right on! Finally. Somebody actually using the brain I gave them.

And/or.

Laughing because, the brain You gave me was faulty. On purpose.

In which case, is this all some kind of cosmic game for You? Which would be pretty crappy on Your part. Still, I can see how You’d need something to counteract the boring, unrelenting goodness of heaven.

To be fair, I should say that, despite my deep reservations about Your existence, I make use of You. I tell my writing students, “Human beings are not only good or only bad. There are no pure heroes or villains. It’s way more messy than that. Creating believable characters is like being God. Imagine Him up there in heaven, creating us one-by-one, setting us in motion. Not controlling us, just rooting for us as we make our way through the world He made. High-fiving St. Peter when we do something good and right.

“Doh!” God says, covering his face with his hands when we blow it. When we’re stupid,

mean, arrogant, stingy, unforgiving—or worse. Always hoping we’ll do better next time.

Maybe this next thought is blasphemous, it probably is—and if so, I apologize. But I truly want to understand. What if You’re just like us—fiction writers, I mean? What if you keep trying and failing to make the world You imagine here on earth?

Like me using the faulty brain You gave me to trick some unanswerable question into a story, hoping against hope that the world I make with words will offer up some small thing that helps me better understand the world You made.

What if each one of us is a story-in-progress?

What if writing a story is a kind of prayer?

Not the kind that asks for favors, but the kind that asks a question—the question always being “Why?”

For example, You may remember that my sister, Jackie, died of brain cancer a while ago. If you are You, all powerful, You decided this would happen to her.

When she called to tell me about the diagnosis, she kept saying in a stunned voice, nothing like her own, “But I’m a good person. A good person.”

And, as You know, she really, truly was.

She was not a religious person. Nor was she an unbeliever. Just one of those live-in-the moment people who didn’t think a lot about such things. In any case, she didn’t have the personal relationship with You that some people describe, the kind in which prayer is like talking to your dad, asking, wheedling, promising to do…whatever if You will just…whatever.

But lots people who claim to know You that way prayed for her.

At first they prayed, “Please make Jackie get better”; then, when it became clear that You’d decided against that, “Please don’t let her suffer any more.”

During her long illness, at her funeral, they said:

God always knows what’s best for us.

(Brain cancer? Please.)

God never gives us more than we can handle.

(But Jackie so could not handle it, God. She lived in terror from the moment of her diagnosis till the hospice nurse gave her enough morphine so that she could finally just slip away. The rest of us didn’t handle it all that well either. We still aren’t.)

God works in mysterious ways.

(Which, I have to say, made me freaking furious every single time and made me want to grab whoever said it and shake the shit out of them, then get right in his or her face and say between clenched teeth, “That is the stupidest, most condescending, thoughtless and annoying thing you could possibly say. Do you actually believe it’s acceptable for God to treat my sister this way—or anyone, for that matter.)

It’s making me freaking furious all over again, writing about it now.

Because, let me tell You, God, it will soon be ten years since I got that awful call from my sister and, as far as I can tell, nothing but heartbreak has come from what You made happen to her.

Just last night I went to the wedding of the daughter of some good friends. We’ve known the bride since she was a little girl, watched her grow into a gawky teenager, and rooted for her as she struggled in those first years after college, trying to find herself, longing for love. Tall, willowy, radiant, she was a picture of happiness in her beautiful gown. After the ceremony, she danced the traditional first dance with her new husband. She danced with her dad. I felt so happy, watching them.

Then the groom danced with his mother.

And it hit me. Jackie won’t be there to dance with her son Sam when he gets married this summer and, God, my heart cracked in a whole new place.

I don’t know. Maybe You feel as bad about this as I do. Maybe when you were writing the story of Jackie, brain cancer just came into it and there was nothing you could do. (That happens with stories, I know.) Maybe you watched it all come down just as I did, hoping for a better, happier ending even knowing how unlikely that would be.

But all this is moot because, as I disclosed earlier, I don’t believe in You.

I believe if there is such a thing as God, He, She, It is nothing like us at all—but so vast and amorphous and truly strange that there are no words, there is nothing in our experience of being human that makes it possible to describe You—and it would be absurd to try.

Here I am talking to You, though—and I have to admit it does feel like I’m talking to Someone. Go figure.

As usual, wrestling with that faulty brain has left me in a muddle, strands of thought tangled hopelessly in my head. As usual, I conclude that all I can do is to keep on writing stories, keep on hoping that each one of them will answer some part of the question, Why?

Why anything, for that matter?

If you are a You, please receive them as prayers.

If you’re not the kind of God equipped to receive anything from us, personally, or if there’s no God at all, nothing but us, and life is no more than some random quirk in the universe, I’ll keep writing stories anyway.

Because I can’t not write and stay even a little bit sane in this crazy world.

Because one of the few things I believe absolutely is that what we learn about ourselves and others writing and reading stories about life on this earth really, really matter.

I remember that letter to God! Still as wonderful now as it was then. Thank you for writing it.

Thanks, Faith. I'd be delighted for you to share. Love you back.