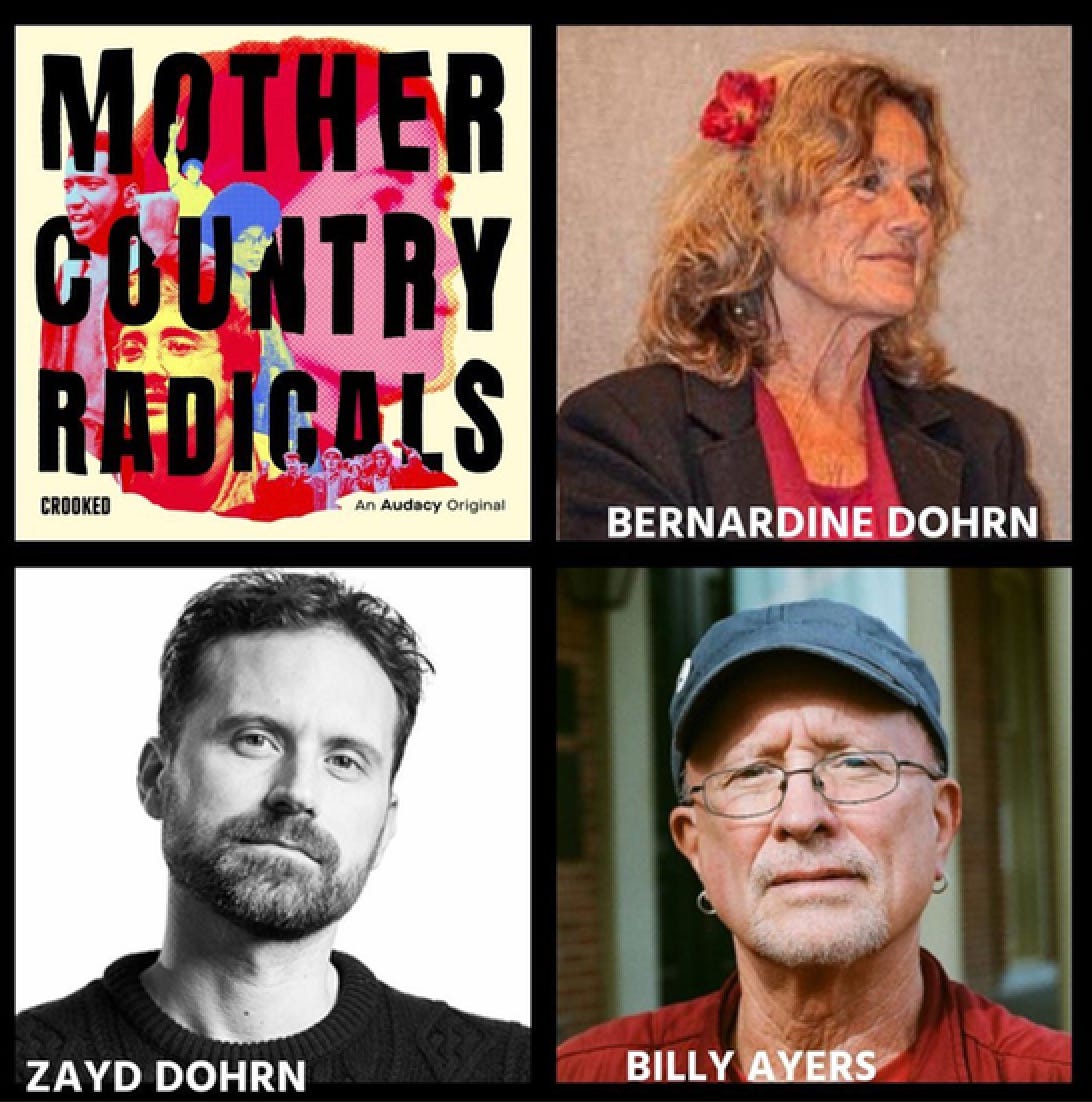

I recently listened to “Mother Country Radicals,” a podcast series hosted by Zayd Ayers Dorhn that explores the legacy of his parents, Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn.

Anyone who knows anything about the 1960s knows Ayers and Dohrn were at the forefront of the antiwar movement, leaders in the Weather Underground, the ultra-radical group that split from the SDS in 1969. They orchestrated the Days of Rage in Chicago and, living underground, committed acts of protest and violence against government buildings and symbols. Along the way, they had two sons—Zayd and Malik—and adopted Chesa, the son of incarcerated Weather activists David Gilbert and Kathy Boudin.

The series is brilliant. Ayers Dohrn speaks honestly about his childhood underground and asks probing questions of his parents and their former comrades. And while many of their actions were, to say the least, questionable in my view, the passion with which they spoke of that time made me remember what it felt like to believe change was possible—

All the more poignant for the terrible time we’re living through right now.

But what hit me hardest was a moment in Episode Ten of the series, “Inheritance,” in which Ayers interviewed several adult children of Weather Underground members. In response to a question about their parents’ decision to have a baby while living as fugitives, one exclaimed, “What were they thinking?”

Amen, I thought.

After which I remembered how little I knew—how little anyone knows—about what it’s like to raise a child before they have one of their own.

“Are you aware that they will eventually become teenagers?” I sometimes ask people when they make the huge decision to have a baby.

Joking.

I’m nuts about babies, I really am. I love learning a new one is on the way.

But they do become teenagers, their world widens in ways you can’t control, and they may or may not begin thinking that maybe there were a few (ha!) things about how you raised them that they’re not all that happy about.

This coming awake from childhood is likely to be even more fraught if you raised them underground.

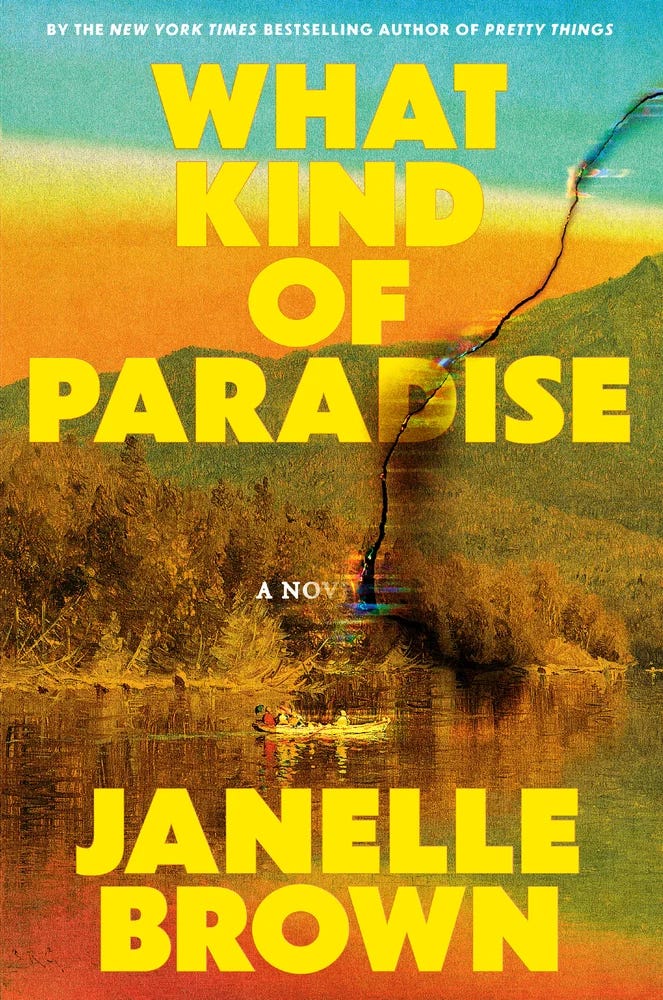

Janelle Brown’s novel What Kind of Paradise begins with a knock on the door: a reporter, who holds out a sketch of a teenage girl that Jane had hoped she’d never see again.

“Is this you?” the reporter asks.

Jane closes her eyes. Behind her lids, she sees, Blood spatters across a shiny red dress. The cold heft of a gun in [her] palm. A tower of flames, bright against the night sky.

“Considering everything that’s happening, I thought maybe you’d want to talk to the press,” the reporter says. “…set the record straight. You haven’t ever told your full story, not since it all went down.”

Jane declines, sends the reporter away. But she finds herself thinking of her own daughter, almost the age she’d been herself when that story began, her “gaze starting to settle on the territories beyond her familiar borders” and knows that for her daughter’s sake—and her own—it’s time to tell her the truth about her life.

“The first thing you have to understand is that my father was my entire world,” she begins.

“Think, Mensa-level genius”.

Saul Williams had engineering, mathematics, and philosophy degrees from Harvard, quit a high-profile job after—according to him—exposing the underlying flaw in their thinking, which they refused to acknowledge. “I could have gotten sixteen patents for inventions,” he told Jane. But he didn’t want to bother with the government bureaucracy.

Think Unabomber—with a kid.

Jane was four when her mother died and her father moved them to a cabin in the Montana wilderness. There, they lived surrounded by towering piles of books and newspapers. They hunted, fished, and kept a vegetable garden and chickens for food, which they cooked on a wood stove. Jane didn’t go to school. Instead, she was “….haphazardly taught some subjects (science, languages) and given college-level instruction in others (philosophy, mathematics, history) and missed others altogether (health and music).” As she grew older, she edited the essays and think pieces her father wrote for Libertaire, a monthly zine he published—and sold through an independent bookstore in Bozeman.

“The New Technological World Order”.

“Power to the SHEEPLE”.

“Dismantling the Autocratic Financial System”.

On Jane’s seventeenth birthday, she wakes to the sound of cursing men, one of them pounding on the door of their cabin. Her father ignores them. There’s a massive bang, a voice yelling “Asshole, we know it was you.” And they’re gone.

When Jane asks her father why he didn’t answer the door he says, “Didn’t think there was much that needed to be said to them, did I?”

“Did you do something she asks?”

He smirks. “What something might you mean? Like, say, sabotaging their equipment by putting sugar in the gas tanks? I suppose someone might have done that.”

From there, Jane is drawn into her father’s increasingly radical attempts to change the course of governmental and corporate forces he believes are responsible for destroying the environment—eventually becoming complicit in an unforgiveable act.

What Kind of Paradise is the story of how Jane comes to terms with what she’s done and, along the way, discovers the truth about the life her father chose for her.

It’s a powerful reminder of the power all parents have over their children and how what we believe shapes them, for better or worse.

What WERE they thinking?!? :-)

This is so good. I love how naturally you bring us into this novel and considering your own connection to the 1960s, I’m looking forward to seeing how this reflects in your own work!